Hundreds of pupils across Cross River State have been left in limbo following the government’s closure of 69 private primary and secondary schools for alleged violations of operational standards.

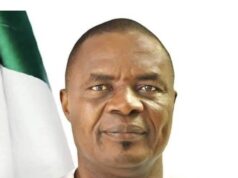

The schools were sealed between October 20 and 21 during an enforcement exercise led by the Commissioner for Education, Senator Stephen Odey, as part of the state’s recently launched Education Reform Policy.

According to government officials, the move was aimed at sanitising the education sector and ensuring that only properly accredited institutions continue to operate.

“We cannot compromise the quality of education in Cross River State,” a senior official in the ministry said.

“Every school must meet the minimum standards set by law before they can teach our children.”

However, the crackdown has sparked outrage among parents and proprietors, who described the timing as abrupt and unfair.

Mrs. Maria Umoh, a mother of four, said the sudden closure has disrupted her children’s learning.

“My four kids have been sent home with no idea when they’ll return to school,” she lamented. “It’s heartbreaking to see them idle while others continue with their lessons.”

Some school owners told DAILY GAZETTE that they were already working to comply with the new regulations when task force officials sealed their premises without prior notice.

They appealed to the government for more time to meet the requirements.

The Education Reform Policy, introduced earlier this month, aims to bring uniformity and structure to the state’s education system.

Among its key provisions are: A harmonised academic calendar for all schools; the exclusive use of ministry-approved textbooks; a ban on merging workbooks with textbooks; regulation of graduation ceremonies to only terminal classes; and strict closing times—1:00 p.m. for primary schools and 2:00 p.m. for secondary schools.

To enforce compliance, two dedicated task forces have been established, one to identify and close illegal schools and another to monitor adherence to the new standards across all local government areas.

Despite the government’s justification, education stakeholders warn that the policy, if not carefully implemented, could worsen educational inequality and leave many pupils without immediate alternatives.

On local radio programmes in Calabar, callers criticised the government’s “sledgehammer approach,” urging authorities to reconsider and adopt a phased compliance strategy that safeguards both quality and access to education.

“Reforms are necessary, but they must be humane,” one commentator said.

“You cannot claim to be protecting education while sending children back to the streets.”